Article in English:

ID: P12.7

Title:

Sound of Silence:

New Art Strategies and Tactics

of Belarusian Artists

Date:

2012

Resource:

Moscow Art Magazine, issue 84, Moscow, Russia

Autor:

Olga Shparaga

Intro:

From January 27th to March 10th, 2012 EFA Project Space (New York) had presented the exhibition of Belarusian artists Sound of Silence: Art During Dictatorship which brought together the works by the most active Belarusian artists created in solidarity with the “silence protests”. As conceived by the curator – Olga Kopenkina – it represented the works of a new generation of Belarusian artists, most of whom have begun their conscious life during the reign of Lukashenko. The exhibition’s title – Sound of Silence – on the one hand, refers to the silent protest sounds, which gathered people in different Belarus cities in spring-summer 2011, on the other hand it calls to take a look at the reverse side of “the life during the dictatorship”.

Sergey Shabohin:

Practices of Subordination,

2012

Practices of Subordination,

2012

Political reality and national symbols

The origins of the critical treatment of young Belarusian artists towards socio-political reality can be seen in the events of the late Soviet era in the Soviet Union.

While at the beginning of the 1990s the first signs of institutionalization of the art community were obvious (such as The Sixth Line gallery and a number of international festivals of contemporary art in Minsk and Vitebsk), then by the end of the 90s on the Belarusian art scene a new trend appeared: galleries were closed, festivals were collapsed, collectives broke up. And the main reason for all these transformations was the consolidation of the authoritarian regime of Alexander Lukashenko.

One of the most distinct reactions to this new political and cultural situation were Ales Pushkin’s performances. Ales Pushkin, as well as the artists Alexander Komarov and Oleg Jushko, belongs to the older generation, on which the political and aesthetic reality of the late 1980s imbued with the spirit of the popular (in those years) National Revival has influenced. Therefore, all three authors work more with theme of collective identity – both national and cultural – rather than with specific time signs.

The main bonding elements of the Belarusian collective identity are the Belarusian language, which become the subject of video research by Alexander Komarov, and flax, with the help of which Oleg Yushko robed all the characters of his installation.While the Belarusian language is a symbol of the construction of the identity from below, the Belarusian regime does everything possible to narrow the sphere of spreading this language and, as it is seen in the series entitled “Implications” by Oleg Jushko, it also actively eliminates the traces of its presence – especially in a common slogan “Long Live Belarus!” – from the facades of houses. Flax, as one of the fashion brands of Belarusian industry, reveals a mechanism of imposition of this identity from above – the dictation of what all the Belarusians should buy 1.

The third, an elder representative of this generation of artists Ales Pushkin constantly uses elements and symbols of the traditional national culture (except for the Belarusian language): this may be the patterns and elements of the Belarusian ornament or the Christian motifs, which he opposes to the political regime of Lukashenko. In 1999 one of the most brilliant performances by Ales Pushkin “Gift to the President” was performed near the Residence of the President of the Republic of Belarus in Minsk, where the artist, dressed in a shirt with a national ornament, brought a cart with manure. Near the unloaded manure Ales, with the help of pitchfork, nailed the portrait of Lukashenko and the inscription “For five years of hard work!” The important part of the most performances by Ales Pushkin is his detention by law enforcement agencies.

Аles Pushkin:

from the series of

performances and

documents,

1998-2002

Belarus as a “critical ontology of ourselves”

The generation of 20-year-old Belarusian artists speaks slightly different language and uses different visual and symbolic tactics. In their interpretations Belarus turns into more complex political, social, economic and everyday reality, which needs punctilious exploration.

Thus, the artists of the group FAU in their installation “Monopoly: The Belarusian Edition” offer to get involved in the sale of Belarusian state and municipal property, which rules are set in favor of governing authority and promote the growth of corruption among its members – close to Lukashenko government officials and businessmen. This installation enters into obvious contradiction with the ideological production of the Belarusian regime, which Marina Naprushkina depicts in her “The Office of Anti-Propaganda”, founded in 2007 in Frankfurt. One of the main slogans of agitation posters – “For Belarus for the sake of people” – is an incentive motive for the artist’s research of peculiarity of the Belarusian “social state”, in which the social has an unenviable role of the silent majority.

However, despite all the wishes and actions of Belarusian government, Belarusian society isn’t reduced to what propaganda says about it. The possibility of new society creation, both in terms of its subjects and mechanisms, is interesting for the creators of the Internet site www.antibrainwash.net, and Nikita Kadan, as well as for the artists Shabohin Sergey, Lena Sulkovskaia, Eugene Shadko and Denis Limonov.

FAU group:

the project “Monopoly”,

2011

Different society: between anonymity and subjectivation

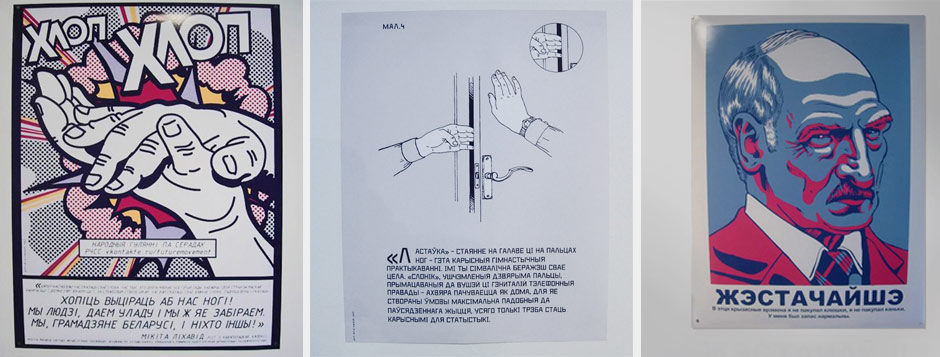

The originality of the project Antibrainwash (www.antibrainwash.net) is that it’s an anonymous union of those who (as you can read on the website) “do not want to live in humiliation and fear”, who care and who are ready to take an active position. The artist’s aim is to help people in it using specific tools – products of visual agitation: leaflets, posters, stickers, as well as stencils for graffiti, which can be printed and distributed for use where it is possible and appropriate: in an entrance, district or in public transport.

Looking at these posters you can compile a list of powerful repressive mechanisms – from rhetorical tricks of speech of the head of the state and ways of conducting gender policy in the country to persecution of independent journalists, closed trials, police brutality, the death penalty, torture in prisons, political prisoners.

An artist Lena Sulkovskaia offers her own version of the topography of this narrative using a certain graphical method detecting and simultaneously concealing the square in front of the Government House (in order to indicate the ambiguity of this place: power and opportunity for its overthrow at the same time).

Another exhibitor Sergey Shabohin transfers the confrontation between repressive power mechanics and social protest tactics to the space of everyday life. His series Practices of Subordination combines various objects of fear. For example, personal items left in parks or ATMs as a symbol of the summer financial crisis in Belarus. One of the connecting parts of these items is a water pipe from the artist’s own apartment, the smell of which, according to his words, symbolizes the rotten socialism in Belarus.

The works of two other young artists in the exhibition – Eugene Shadko and Marina Naprushkina – present two different versions of subjectivation: through the personification of protest political reality (in Shadko’s work), and through the personal identification with the “face” of the Belarusian State (Naprushkina). Thus, Eugene Shadko depicts in his work a teenager with long hair hiding his face and with the photo of a political prisoner Dmitry Dashkevich (one of the young political activists) on his chest. Naprushkina Marina in her film “Patriot” walks in Minsk with the portrait of Lukashenko.

The strategy of subjectivation and personalization of Belarusian society reaches its culmination in Denis Limonov’s “Letter to the Prosecutor General of Belarus”. In this letter, the artist claims the involvement of Art Group “Lime Blossom” (he is the leader of this group) in the series of bomb blasts in Belarus public places during the period from 2005 to 2011 when the tragedy in the Minsk subway was occurred where fifteen people were killed and more than two hundred were injured (the accused of the organization of the last terrorist attack were executed in March 2012).

The works of two other young artists in the exhibition – Eugene Shadko and Marina Naprushkina – present two different versions of subjectivation: through the personification of protest political reality (in Shadko’s work), and through the personal identification with the “face” of the Belarusian State (Naprushkina). Thus, Eugene Shadko depicts in his work a teenager with long hair hiding his face and with the photo of a political prisoner Dmitry Dashkevich (one of the young political activists) on his chest. Naprushkina Marina in her film “Patriot” walks in Minsk with the portrait of Lukashenko.

The strategy of subjectivation and personalization of Belarusian society reaches its culmination in Denis Limonov’s “Letter to the Prosecutor General of Belarus”. In this letter, the artist claims the involvement of Art Group “Lime Blossom” (he is the leader of this group) in the series of bomb blasts in Belarus public places during the period from 2005 to 2011 when the tragedy in the Minsk subway was occurred where fifteen people were killed and more than two hundred were injured (the accused of the organization of the last terrorist attack were executed in March 2012).

In this letter the artist also acknowledges the connection of his art group with some terrorist groups of European countries. He also mentions that the motive for his actions (which he considers artworks) is the prevention of “large-scale political terror” and “drawing public attention to the problem of constitutional fascism in the republic” with the help of local actions.

Antibrainwash project,

central poster —

drawing by Nikita Kadan

“The personal is political”

Another Belarusian reality the younger generation of Belarusian artists work with is composed of a series of oppositions: on the one hand, the series of “physics” (quite traditional forms of coercion) and “microphysics” of authority (invisible and dispersed forms of control), and a set of strategies of resistance on the other hand. The first one is associated with humiliation and fear, and the other – with protest, active position and solidarity.

Young Belarusian artists offer other active participants of social life (researchers or counter-elites members) new strategies and tactics, which take form of thorough work with specific social dimensions and phenomena.

At the same time everyday reality becomes a source of inspiration. It is important that it tends to personification and subjectivation related to its own biography and destiny. The young generation of Belarusian artists seemed to put a new meaning to the feminist slogan “the personal is political”, thereby a new private (the opposition to one person and his subordinate impersonal device) and a new political (a variety of practices of social participation and local actions, a manifestation of solidarity) is born.

Marina Naprushkina,

The Office for Anti-propaganda,

2009-2012

Notes:

1 Belarusian intellectual Almira Ousmanova considers the slogan “Let’s Buy Belarusian!” a symbol of construction (by the government) the nation not as a community of tradition, language and history, but as “the community of practice of consumption.”